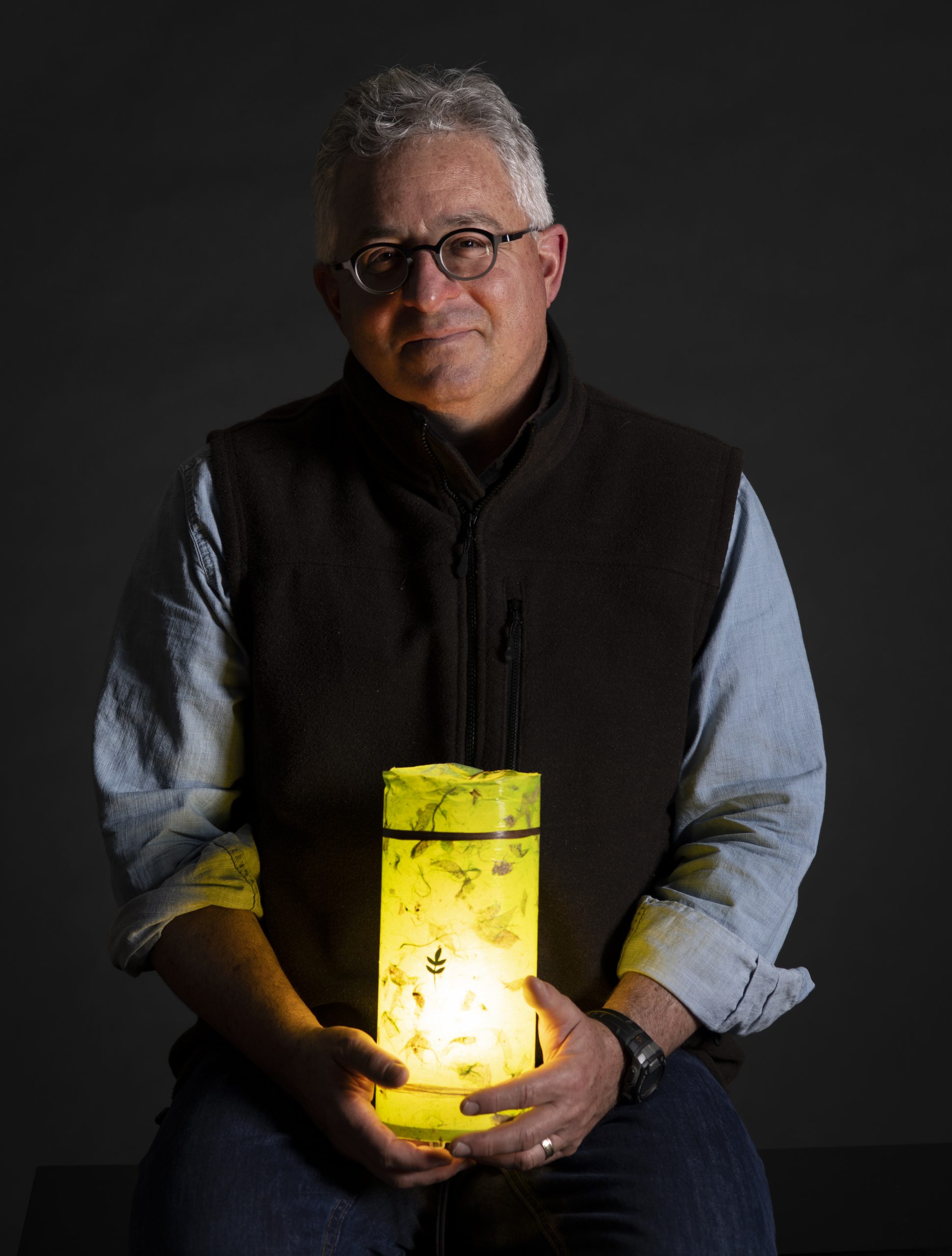

Irwin Goldman

Light #31

I cannot imagine my presence here without randomness; without sheer chance.

It’s hard to reconcile the simple fact that the family history I can describe, which comprises a bit less than 200 years, represents an incredibly tiny slice of time. The earth itself is five billion years old. Millions of years ago, Illinois was a shallow sea. Thousands of years ago, Wisconsin was covered by glaciers. Some time in the early part of the 19th century, Mordecai Wilensky was making linseed oil in a shtetl known as Derhichen, near Pinsk, in what is today Belarus. His daughter married Yitzhak Goldman, and at this point I can begin to trace the Goldman family through the arc of seven generations as they came to America. This is also the period in which Menachem Mendel Zussman was raising his family in the tiny town of Horoduk, near Minsk. One of these Zussmans, Aaron, came to America to begin a new life and gave rise to the Zussmans of Wisconsin. It is also hard to reconcile the fact that the Jewish people have had somewhat less than 200 generations since Abraham’s time, in 2000 BCE, as he hiked up Mount Moriah to sacrifice his son Isaac.

The role of contingency is overwhelming. How could it be that I was fortunate enough to have been born to a branch of the family that survived, allowing me to participate in the six million lights workshop with David Moss, a relative through the marriage of my brother, in Madison, Wisconsin in 2019. How could it be that my Goldman and Zussman ancestors were prescient enough to leave Eastern Europe for middle America at the turn of the 20th century; leaving behind what would be the horrors of the holocaust and the destruction of their remaining families and their people? How could it be that within the span of just a few months in 2019, I was able to travel back to Belarus and Poland with my brother to see these shtetls from where we came, and then to commemorate those whose lives were lost there in this workshop?

Sometimes contingencies lead to destruction; other times rebuilding. I found the lights that we made in this workshop to be remarkably healing and beautiful, as if we were repairing something that had been so badly broken. It made me think of this quote from the very last page of Walden, to which I return every year at this time:

“Who knows what beautiful and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society, deposited at first in the alburnum of the green and living tree, which has been gradually converted into the semblance of its well-seasoned tomb — heard perchance gnawing out now for years by the astonished family of man, as they sat round the festive board — may unexpectedly come forth from amidst society’s most trivial and handselled furniture, to enjoy its perfect summer life at last!”